15. Blawenburg Tavern

- David Cochran

- Mar 18, 2019

- 6 min read

Updated: Jun 19, 2019

Blawenburg Tavern has been the Hartshorne home for 60 years.

When it comes to success in real estate (and many other things in life) timing is critical. William M. Griggs must have had a strong hunch that it was time to build some houses and other services on the vacant acreage between the Van Zandt farm and the Covenhoven farm. He knew that the Georgetown-Franklin Turnpike had been approved by the State of New Jersey and that the rugged road that passed through Blawenburg along the ridge was scheduled to be improved.

He also knew that the building of a bridge across the Delaware River from New Hope to Lambertville would greatly increase the traffic on the planned turnpike. Travelers would need services – a place to eat and rest, a blacksmith shop to make horse and carriage repairs, and a general store for local residents and travelers. Griggs’s wife, Catherine, was the great-granddaughter of John Covenhoven who built his farmstead in 1757. Her mother, Susannah Stout, agreed to sell William and Catherine Griggs 100 acres that encompassed what would become the village and the road that bisected it. It was a developer’s dream come true.

The first thing they decided to build was a home for themselves that could also begin to serve the new passengers that would be traveling before their door. They decided that a multi-purpose tavern would be a good first building in Blawenburg Village.

Griggs did some marketing research and noted that the closest tavern was in Stoutsburg (aka Dogtown), two miles west of Blawenburg at Province Line Road, the road that divided east and west Jersey. There wasn’t another tavern to the east until you got to Rocky Hill. By horse and buggy on unimproved roads, this was a bit of a trek. He figured that a tavern would be a good investment, so they built the home in 1817 and opened the tavern in 1818.

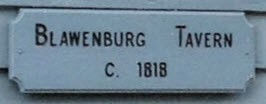

This sign appears on the outside of the Hartshorne home today.

A 19th Century Rest Stop

In earlier times, taverns were not just places to go for food and drink. They served as all-purpose meeting areas, sometimes as post offices, convenience stores, courtrooms, and inns. In the case of Blawenburg Tavern, its function was dictated by its location. It was on a main route from Philadelphia to New York, so it was a logical stop for stagecoaches that crossed the Delaware at New Hope. Such stops weren’t just for the passengers. The horses had to be changed out periodically and allowed to rest before they continued their journey pulling a different stagecoach.

Blawenburg Tavern was the 19th century version of a turnpike rest stop, providing food and beverage, a privy (outhouse), and even an overnight stay for weary travelers. But the tavern also served the township as a meeting place for officials. The Montgomery Township Committee reportedly met at the tavern in 1827 for their annual meeting.

While the tavern ceased operation more than a century ago, its elegance has been preserved by its various owners over the years. It has been a source of many memories by its residents as we see in this recollection by Annie Allen of her life growing up in the former tavern.

This green barn was attached to the tavern and used as a kitchen until sometime in the early 20th century. It is on the back of the Hartshorne property today.

Growing Up in Blawenburg Tavern

By Annie Hartshorne Allen

I was six. My family and I had moved from Brooklyn Heights and this was our new home. A country town, cows across the street, dirt sidewalks and houses full of children - my age, younger and older. Boys and girls all living in the same town, going to the same school. Heaven!

My three-year-old sister and I shared a bedroom. We had our own fireplace complete with mantlepiece and stone hearth, used so long ago when our house served as the only town tavern for miles around. The floor boards were made of wide pine planks and the windows that looked out on the street featured colonial trim and prominent sashes. The rooms afforded us little storage space. One deep cupboard served as our closet to put everything we owned and valued. A metal black grate in the floor allowed a smidgen of heat to enter our room from downstairs. In the winter, the water from the upstairs bathroom faucet would freeze overnight. We could see our breath. The old house breathed and we learned to breathe with it.

My little brother, one-year-old, had his own room across the hall. That room was newer, part of the addition that had been added long after the tavern had closed its doors. I liked his room because it had a large, long closet with sliding doors. The windows of his room looked out onto our big yard and the ramshackle barn at the end of our driveway.

My mother and father’s bedroom, part of the original structure, also had wide pine floor boards, two large, colonial trimmed windows which flooded their room with morning light. Their only closet, like ours, was merely a shallow indentation in the wall displaying flowered wallpaper from years past, a few hooks, and enough room for my mother to hang her clothes. My father made do with a bureau and makeshift closet in the hallway. A corner door in my parents’ room led to the attic which became our secret hideaway where we created forts and set up clubhouses when friends came over.

As we settled into our new home, my mother’s belly began to grow larger. When my little sister finally arrived, she was housed in the pocket-sized room wedged between my parents’ and our rooms. In this tiny space there was only enough room for a crib, a rocking chair and a small bureau. We never knew what this mysterious little room had been used for back in the tavern days. Perhaps a storage area for alcohol, suitcases or both. My sister lived happily in that room for many years to come.

The cellar, dark and damp, was another frontier. A simple rope banister led down the rickety, old steps. The dirt floor, cobwebbed corners, and the wide expanse of space served as another potential fort. There was a secret escape hatch, a trap door just above the ancient coal chute, which led to the outside of the house. This trap door became the entry and exit for “invading armies” and “prisoners” who had been kept in the cellar dungeon.

The tavern is shown on the left with the kitchen still attached in 1907. All the buildings on the right side of the picture were constructed after the tavern.

The barn, a makeshift, patched together structure at the end of the driveway, had been the original kitchen of the tavern. It had been inexplicably moved to the back of the property in the early 20th century. A simple tongue and groove tool shed, a home for rakes, pitchforks and shovels of every size, had at some point been attached to the barn.

Over the years this barn became more and more dear to me. Standing in its center, gazing up at patches of faded wallpaper, I loved what this old structure had once been. Then, looking around at my father’s workbench and the pile of neatly stacked firewood, I loved what it had become.

This house, the first to be built in our village of Blawenburg, has been home and refuge to our family for sixty years. It has always been there for us, offering its womb-like warmth whenever I returned as a child in grammar school, a young college student, a mother of three, and a middle-aged woman. It continues to stand proudly, ready to embrace and protect my family and the families to come.

Annie Allen has lived in Blawenburg most of her life and has fond memories of growing up in the tavern.

This sketch of Blawenburg Tavern appears in Historic Sites & Districts in Somerset County, New Jersey: Listed on the National and New Jersey Registers of Historic Places.

The first non-farmhouse in Blawenburg is now more than 200 years old. It stands in regal elegance near the crossroads in Blawenburg as a source of pride for the village and admiration of travelers. If only these walls could talk, there would be many tales of Blawenburg to tell.

Blawenburg Fact:

When the first settlers arrived in Blawenburg in the late 1730s, they must have felt at home with their Dutch neighbors. In fact, they may have been related to many of them. According to Cornelius C. Vermeule in The Genealogical Magazine of New Jersey (October, 1928), a 1737 census showed that the population of white residents in Somerset County was 4,505 with 4,250 estimated to be Dutch. Of course, there were many slaves who were not taken into account in this census.

Looking Ahead:

Blog 16. When the KKK Visited Blawenburg

Blawenburg made it to the New York Times after a KKK paid a visit to Blawenburg in 1923.

Sources:

Brecknell, Ursula C., Montgomery Township, An Historic Community, 1702-1972, Van Harlingen Historical Society, Montgomery Township, NJ, 2006.

Vermeule, Cornelius C. “Influence of the Netherlandish People in New Jersey,” The Genealogical Magazine of New Jersey, Volume IV, No. 2, October, 1928.

Photo Credits

Tavern sketch - Historic Sites & Districts in Somerset County, New Jersey: Listed on the National and New Jersey Registers of Historic Places, Somerset County. Somerville, Cultural & Heritage Commission, 2015.

Tavern picture and sign – David Cochran

Green barn – Rev. Jeff Knol

Crossroads image – From an old postcard

Comments